Thylacine: Bringing the past to life

Scientific efforts to resurrect the extinct thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, are remarkable and spark wonder that everything is possible.

Humankind is gearing up for a Mars space mission and AI is changing how we reason and work, but the deployment of genetic science to bring a species back from the dead surpasses them all.

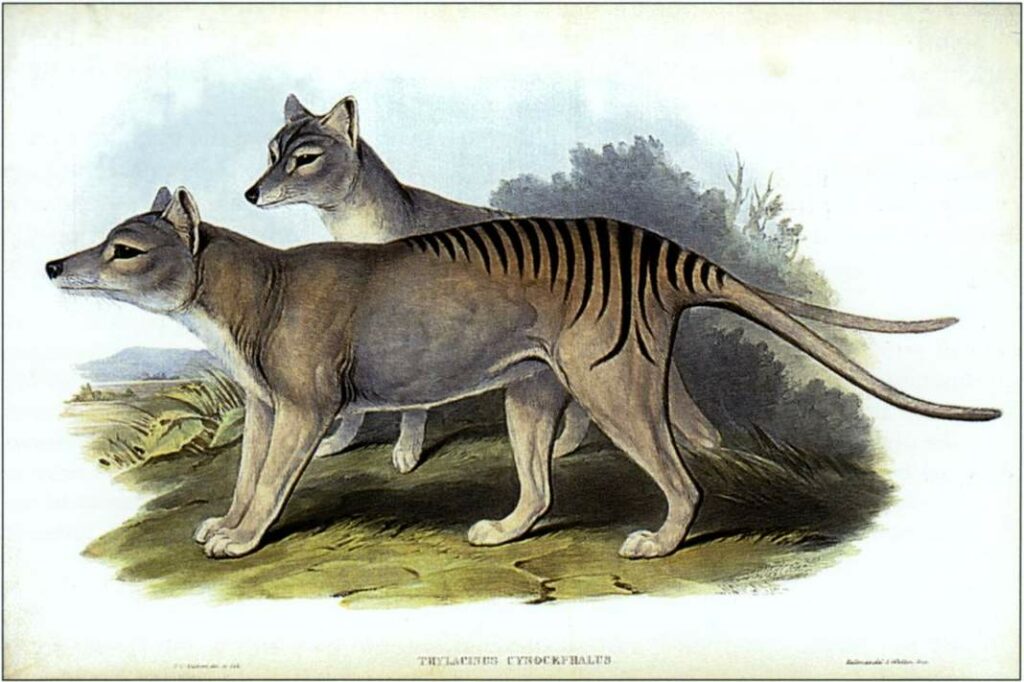

The thylacine once roamed the forests of Tasmania as an apex predator — a striking marsupial with wolf-like features, tiger-like stripes, and a jaw that could open wider than any other mammal.

Tragically, this unique species was driven to extinction by human persecution. The last known thylacine died in captivity in 1936, marking the end of a lineage that had thrived for thousands of years.

Today, scientists are working to reverse this loss, blending cutting-edge genetics with conservation vision to bring the thylacine back to life.

The thylacine’s legacy

The thylacine was a marvel of evolution. As a carnivorous marsupial, it filled an ecological niche similar to wolves or big cats, preying on kangaroos, wallabies, and other small mammals.

Its extinction left a gap in Tasmania’s ecosystem, contributing to imbalances such as overpopulation of invasive species like rabbits and the spread of diseases like Devil Facial Tumor Disease in Tasmanian devils.

European settlers demonised the thylacine as a livestock predator, leading to government-funded bounties that decimated its population by the early 20th century.

The science of de-extinction

Modern science offers a second chance. Spearheaded by Colossal Biosciences and the University of Melbourne’s TIGRR Lab (Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research), researchers are using CRISPR gene-editing technology to reconstruct the thylacine’s genome from preserved DNA.

The fat-tailed dunnart (a tiny, mouse-sized marsupial and the thylacine’s closest living relative) serves as both a genetic template and a surrogate parent.

The process involves:

- Sequencing the thylacine genome from museum specimens.

- Editing dunnart stem cells to align with thylacine DNA.

- Implanting engineered embryos into artificial wombs or surrogate dunnarts.

This ground-breaking work could yield the first thylacine joey within a decade. Beyond resurrection, the project aims to advance marsupial conservation tools, such as stem cell “bio-banking” and assisted reproduction, which could protect endangered species like the Tasmanian devil.

Ethical horizons

While the science is exciting, ethical questions need to be addressed. Critics argue that de-extinction risks diverting resources from conserving existing species.

Others question whether revived thylacines could adapt to modern ecosystems altered by climate change and human activity.

And most seriously, if this scientific breakthrough could be deployed in less beneficial ways, how do we prevent this?

In my view, the ethical considerations weigh in favour of resurrecting the thylacine.

Professor Andrew Pask, lead scientist at TIGRR Lab, acknowledges: “Our work must be guided by humility. We’re not just rebuilding a species; we’re rebuilding an ecological relationship.”

There’s also the symbolic weight of correcting past wrongs. The thylacine’s extinction was a direct result of human failings, and its revival could become a beacon for restorative conservation.

By reintroducing the thylacine to its former habitat, scientists hope to rebalance ecosystems and inspire global efforts to protect biodiversity.

A future of possibilities

De-extinction is more than a scientific feat, it’s a moral reckoning. The thylacine project underscores humanity’s growing ability to repair ecological damage, but it also demands careful stewardship.

As we venture into this new frontier, balancing innovation with ethical responsibility will be key.

In the words of Colossal Biosciences: “Extinction is a colossal problem. But with creativity and care, it might not have to be forever”.

The thylacine’s return could mark a turning point, proving that science, when guided by respect for nature, can truly bring the past to life, for the benefit of all.